|

The prosecution’s decision to abandon its appeal in the Daejang-dong land development scandal is fueling criticism that the “independence from political power” once promised by prosecutorial reform has drifted even further out of reach.

In a case that could potentially implicate President Lee Jae-myung, an appeal that had already cleared all internal approval procedures was ultimately not filed because of an order from the top leadership. On Sunday, Kim Young-seok, a prosecutor in the First Inspection Division at the Supreme Prosecutors’ Office, issued a rare public rebuke, saying, “The deputy prosecutor general, the head of the anti-corruption division and the chief of the Seoul Central District Prosecutors’ Office have betrayed their consciences as prosecutors.” Critics argue that even after years of reform driven by the progressive camp, the independence and command structure of the prosecution remain shaky.

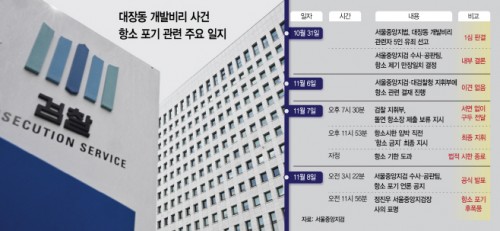

On November 7, the Seoul Central District Prosecutors’ Office decided not to appeal the first-instance verdicts for Yoo Dong-gyu, former planning director at Seongnam Development Corporation, and five private-sector businessmen including Kim Man-bae, the major shareholder of Hwacheon Daeyu, who were indicted over the Daejang-dong development scandal. The hours leading up to the appeal deadline that night were tense inside the prosecution.

The investigation team had already completed the internal approval process for filing an appeal, with sign-offs from the senior prosecutor, the fourth deputy chief and the chief prosecutor. But about four hours before the deadline, the Supreme Prosecutors’ Office suddenly ordered a “re-examination,” and just seven minutes before the cutoff it issued a final decision not to allow the appeal. As a result, the appeal was never filed. At 3:22 a.m. the next day, the investigation team took the unusual step of issuing a press notice, strongly voicing its opposition, and just eight hours later, Seoul Central District Prosecutor General Jung Jin-woo tendered his resignation.

Because the prosecution declined to appeal, the appellate court will now only review the points raised by the defendants, who claim they were unfairly convicted. Under the Criminal Procedure Act’s “principle of prohibition of disadvantageous change,” if the prosecution does not file an appeal, the higher court cannot impose a heavier sentence than that of the lower court. In effect, only the defendants will enjoy the full benefits of the three-tier trial system, while the prosecution has voluntarily confined itself to a single-instance outcome.

The prosecution has also lost its chance to seek recovery of what it claimed were illicit gains running into the hundreds of billions of won. In the Daejang-dong project, Seongnam Development Corporation took in 183 billion won, while private developers reaped profits of 788.6 billion won. Prosecutors argued this entire amount constituted unjust enrichment and sought its full confiscation. However, the first-instance court ruled that the loss could not be clearly calculated and convicted them of breach of duty under the Criminal Act, not aggravated breach of trust under the Act on the Aggravated Punishment of Specific Economic Crimes. The recognized amount of loss was thus limited to 47.3 billion won.

Within the prosecution, suspicions have surfaced that the Ministry of Justice “interfered politically” in the case by offering so-called “opinions” to the Supreme Prosecutors’ Office and the Seoul Central District Prosecutors’ Office. Acting Prosecutor General Noh Man-seok dismissed such claims on Sunday, saying the decision was made “after careful deliberation” and denying any involvement by the ministry. Prosecutor General Jung, however, drew a line, saying, “While I accept the decision of the Supreme Prosecutors’ Office, the position of the Seoul Central District Prosecutors’ Office was different,” and added that he was stepping down “to take responsibility for this situation.”

The core issue is that if the Ministry of Justice intervened in any form — whether through a formal investigative directive or an “expression of opinion” — it would be difficult to avoid controversy over political meddling in prosecutorial affairs.

The Daejang-dong case is closely intertwined with President Lee’s trial, which is currently on hold. In March 2023, prosecutors indicted Lee over the Daejang-dong development scandal, describing him as being at “the apex of collusion between politics and business.” While the first-instance court characterized the case as “a corruption crime committed on the basis of a long-standing relationship of collusion backed by sustained provision of money,” it withheld judgment on Lee’s involvement.

Contrary to Lee’s longstanding insistence that Daejang-dong was a “model public-interest project,” the court explicitly stated that the project “caused financial harm to the city of Seongnam,” prompting speculation that the ruling could influence any future resumption of his trial.

Observers say that the more politically charged a case is, the more independently the prosecution’s decision-making on appeals must operate. Article 7(1) of the Prosecutors’ Office Act stipulates that “a prosecutor shall comply with the instructions and supervision of his or her superior,” but paragraph 2 provides that “if a prosecutor has a different view on the legitimacy or propriety of such instructions and supervision, the prosecutor may raise an objection.” Despite this, the prosecution did not initiate any formal objection procedure. As a result, the internal check-and-balance mechanism guaranteed by law failed to function, and the prosecution is now facing criticism that it did not defend its own institutional independence.

Inside the organization, there is also backlash: “Is it called independence only when a particular camp benefits, and anti-reform when it does not?” one official at the Seoul Central District Prosecutors’ Office said. “After debates over abolishing the prosecution service and a bruising round of parliamentary audits, the sense of powerlessness at the top is at its peak, and front-line prosecutors watching all this have become deeply cynical,” the official added, noting that “in private, harsh criticism that the leadership is ‘pathetic’ is rampant.”

Former prosecutor and now lawyer Lim Moo-young also weighed in, saying, “If Prosecutor General Jung was going to resign, he should at least have enabled the investigation team to file the appeal first and then taken responsibility.”

Most Read

-

1

-

2

-

3

-

4

-

5

-

6

-

7