A VISIT TO THE RICORDI ARCHIVE (Archivio Storico Ricordi)

|

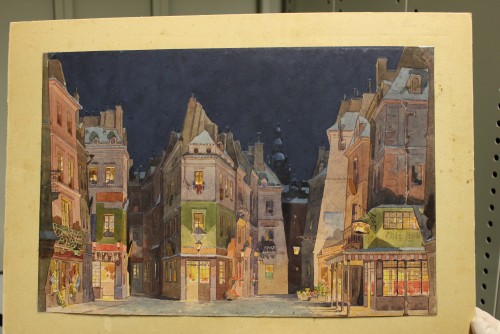

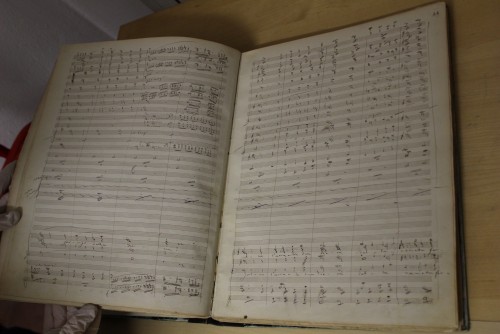

| Puccini's La boheme premiere stage sketches./ Photo by Sohn soo yeon |

The Italian phrase “Archivo Storico Ricordi” refers to Casa Ricordi’s 200 year-old archive of documents and collections. This archive lives within the antique 14th century walls of the Palazzo Brera in Milan, one of the Italy’s most prominent museums alongside the Vatican Museums and the Uffizi Gallery in Florence.

Home to not only the Ricordi Archive but also several other cultural institutions such as the art academy and gallery of the city, the Palazzo Brera embraced me with its aura of artistic eminence the moment I stepped into the entrance courtyard. Due to the museum’s substantial size and complex structure, the director of Ricordi Archive led the way through narrow hallways, past several libraries filled with ancient books to the brim. Only after series of twists and turns did I catch my first glimpse at the Ricordi Archive, tucked away near the heart of the museum.

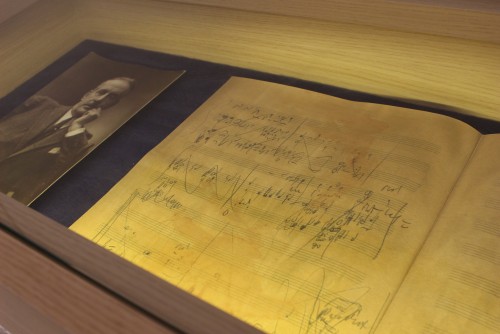

The Ricordi Archive displayed its legacy not by the size of its space nor staff, but rather the gems it had been safekeeping for centuries. A clear glass box that stood alone in the center of the office caught my eye--the handwritten original score of Turandot, penned by Puccini himself.

|

| Puccini's Turandot sheet music at the end./ Photo by Sohn soo yeon |

As captured in many of his photographs, Puccini was a habitual smoker of Toscano cigars and cigarettes. In 1924, a diagnosis of laryngeal cancer led him to seek medical treatment in Brussels, where he soon passed away from a heart attack. Prior to taking his train to Brussels, Puccini added his very last scene in Turandot, having Prince Calaf’s maid Ryu commit suicide. Had he returned from his trip, Puccini would most likely have finished the opera as the La Scala Opera House (Teatro alla Scala) and its conductor Arturo Toscanini were anxiously waiting to produce this eccentric new opera that was set in China. However, Puccini never returned and Turandot was left unfinished.

Although the opera was later finished by Puccini’s student Franco Alfano, it is without a doubt that the score lacked the original composer’s finishing touches--performances of Turandot today are often performed in its unfinished form, or revised with an alternate ending. Even Torino’s Royal Theater (Teatro Regio Torino) orchestra ended its last note at Ryu’s death at its most recent performance of the opera.

There it was, the unfortunate fate of Turandot before my very own eyes. The pages were discolored with coffee and the tobacco debris from its owner. The bare sight of this rather shabby document, the tragedy of a extraordinary composer embedded in its notes and scribbles, was almost bewitching.

|

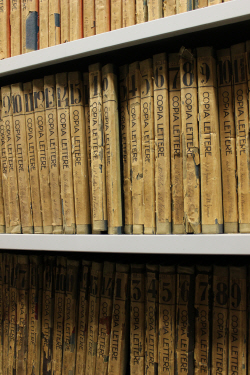

| Carefully arranged bundles of individual letters./ Photo by Sohn soo yeon |

Row after row and column after column, the Ricordi Archives exhibited detailed documentation of the development of opera from its inception to modern day. This included not only the original scores of operas, but also detailed records of contracts with Casa Ricordi, stage sketches, and even samples of designed costumes and props. The degree of thorough precision was beyond striking--thousands of related news clippings as well as letters to and from Casa Ricordi was meticulously documented, down to the last business card.

Ricordi Archives’ staff adhered to equally high standards as they thoroughly catalogued documents in the humidity- and temperature-controlled storage rooms. Each document was personally handled with gloves by the head curator as he impeccably recited facts about it. The curator’s expert reading and translation of what seemed to be Puccini’s indecipherable handwriting provided a small glimpse of the incredible research that took place here.

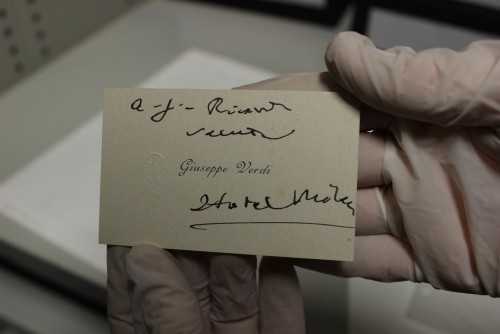

Perhaps the most memorable relic I stumbled upon was Verdi’s name card, one that only contained his name. Imagine the audacity and ingenuity it would take for one to present oneself with nothing but a name. Whenever Verdi traveled to Milan from his villa in Sant’Agata near his hometown, he would check in at the Grand Hotel and pen the word “arrival” on his name card before having a messenger deliver it to Casa Ricordi. Centuries later, the same name card now embodies his terse yet charismatic spirit.

|

| Verdi's business card./ Photo by Sohn soo yeon |

Puccini, on the other hand, revealed a drastically different personality in his letters to Giulio Ricordi from New York. In numerous pages of unintelligible penmanship, Puccini recounts in great detail the current status of operas in New York, the warm hospitality he has been receiving, and most importantly the overwhelmingly positive feedback his work attracted. As mentioned previously, unlike Puccini who composed with his indecipherable handwriting, Verdi diligently completed his work to perfection, fit to be performed without delay. The incompatible differences in music and personality between the two composers are carefully documented within the stacks of Casa Ricordi.

Moreover, the collections of images of Verdi and Puccini’s debut performances--the assortments varying from stage sketches to costumes and props--could have stood as oeuvres d’art alone. These sketches serve as priceless resources when creating such operas with over 200 years of history. Due to Ricordi Archives’ extensive documentation practices, even the seemingly extraneous illustrations of jewelry can be traced to the very scene it was utilized in.

The comprehensive financial records of Casa Ricordi also bear indispensable information regarding the opera industry’s status within Italy. Employment contracts with countless composers, writers, conductors, singers and staff, have helped historians better gauge the allocation of national cultural funds to the opera industry. A closer look at the company ledgers also revealed that Casa Ricordi was the first publisher to pay its composers additional royalties depending on box office success.

|

| The part of Verdi's choir of the hebrew salves, from Nabucco in his own handwriting./ Photo by Sohn soo yeon |

Having spent three wondrous hours inside the Ricordi Archives, I left the museum, speechless. As an opera critic and educator, I had great difficulty discerning whether I was more overwhelmed by having discovered hidden treasures of Italian opera or honored to have personally inspected the remaining remnants of historical art and music.

As the Ricordi Archives proceeds with its preservation efforts and research, the Italian opera also continues to develop and progress. With 200 years of opera and music history as its foundation, the Ricordi Archives influences the direction of opera throughout Italy as well as the rest of the world.

The great and brilliant legacy of opera’s history remains very much alive.

Translation. Betty Heeso Kim

|

Most Read

-

1

-

2

-

3

-

4

-

5

-

6

-

7