|

AsiaToday reporters Lee Ji-hoon & Son Cha-min

The South Korean economy is rapidly recovering this year to pre-pandemic levels. The economic growth forecast, which is a comprehensive report of the economy, is continuously being revised upwards backed by strong export growth. However, it is uncertain whether such growth will continue in the second half of the year. This is because the real economy can be restored only when employment rate is recovered along with exports, but the number of quality jobs is declining. Besides, low vaccination rates and inflationary pressures are also considered as key variables.

The South Korean economy is forecast to grow 3.8 percent this year, the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development said Monday, ramping up its previous projection of 3.3 percent.

Previously, the Bank of Korea (BOK) revised up its growth outlook for the country this year by 1 percentage point to 4.0 percent while the Korea Capital Market Institute also raised it by 1 percentage point from 3.3 percent to 4.3 percent.

The country’s export was the main factor behind the subsequent upward revision of the growth rate. South Korea’s export amounted to 50.73 billion U.S. dollars in May, up 45.6 percent from the same month of last year, according to the Ministry of Trade, Industry and Energy on Tuesday. It was the fastest increase in over 32 years. It was the first time that the country’s export surged more than 40 percent for two months in a row. This is due to strong performance of major export items, such as semiconductors and automobiles amid the global economic recovery.

“Exports play a very important role in the South Korean economy, which is highly dependent on external sources,” said Lee In-ho, an economics professor at Seoul National University. “Exports are expected to proceed positively as the global economy has recently improved significantly, mainly in advanced countries,” Lee said.

However, the concern is that employment is not catching up with economic growth. Only when more jobs are created can the people feel the economic recovery and the domestic economy revives as well.

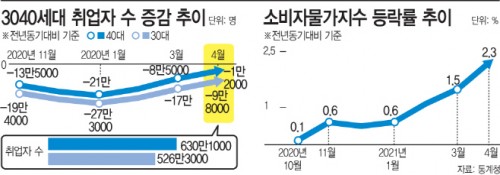

According to the BOK, employment is projected to increase by 140,000 this year. It was higher than the previous forecast of 80,000, but the figure is not satisfactory considering last year’s job losses of 220,000. Besides, the number of quality jobs is decreasing. The number of those employed totaled 27,214,000 in April, up 652,000 from the same month of last year, according to Statistics Korea. However, employment among those in their 30s and 40s, the backbone of the Korean economy, declined 98,000 and 12,000 each.

“The government must quickly change its employment policies in a direction where private companies can create jobs,” said Kim Tae-gi, an economics professor at Dankook University. “This will change the employment situation in the future,” he said.

In addition, the vaccination rate, which barely surpassed the 10% range, is also considered to be a factor holding back the economy recovery. A total of 5,791,503 people, about 11.2 percent of the population, have received their first jabs of COVID-19 vaccines so far, according to the Korea Disease Control and Prevention Agency. The projection of people who have gotten their second shots stands at 4.2 percent. Rapid vaccination may lead to a rebound in private consumption and domestic demand, but there seems to be still a long way to go.

“South Korea’s vaccination rate is below the global average, which is holding back the economic recovery,” said Yang Joon-mo, an economics professor at Yonsei University. “Polarization may occur as vaccine dissemination is delayed,” he added.

The OECD pointed to a relatively slow pace of vaccination in South Korea compared to many member nations and advised the government to accelerate inoculation to remove potential hurdles in the recovery of domestic consumption and employment.

At the same time, inflationary pressure is increasing uncertainty in the Korean economy. The government’s expansionary finances have played a role in the basis of recent economic growth. The government’s financial aid helps low-income families to survive the pandemic aftermath, but the increased money supply also increases the possibility of inflation. When inflation exceeds the price target, central banks are forced to raise interest rates and curtail quantitative easing.

#Employment #vaccine #inflation #Korean economy #economic growth

Copyright by Asiatoday

Most Read

-

1

-

2

-

3

-

4

-

5

-

6

-

7