|

As South Korea enters 2026, calls to revise the Constitution are resurfacing, though observers warn that meaningful progress will remain elusive without bipartisan cooperation.

The National Assembly last year was widely criticized for being mired in partisan conflict, with little evidence of cross-party collaboration. Analysts argue that lawmakers must undertake painful reforms to refocus on livelihood and economic issues, with constitutional revision increasingly cited as a potential starting point.

According to political circles, the Assembly has often acted as an “instigator of conflict” across generational, gender, and partisan lines. Issues such as pension reform, the 52-hour workweek, recurring gender disputes during election seasons, and controversies over prosecutorial and judicial reform fueled heated debates. Yet critics say Parliament largely reduced these issues to blame games rather than offering solutions.

The constitutional amendment debate—raised at the start of many new years only to fade—has returned amid arguments that the current system’s “imperial presidency” and winner-takes-all structure can no longer be ignored. While both major parties broadly agree that the 1987 Constitution no longer reflects contemporary realities, a concrete legislative roadmap remains absent.

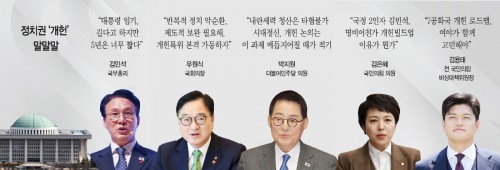

President Lee Jae-myung has repeatedly mentioned constitutional reform, both during his campaign and after taking office, listing it as a top national agenda item. Prime Minister Kim Min-seok recently drew criticism from the opposition after remarking that a five-year presidential term is “too short.” Lawmaker Kim Eun-hye of the People Power Party rebuked the comments as provocative, questioning whether they signaled a push toward a four-year, two-term system ahead of local elections. The opposition, meanwhile, remains wary of framing the debate as a bid for long-term rule.

National Assembly Speaker Woo Won-shik has been the most vocal proponent, urging floor leaders from both parties to formally launch a constitutional revision committee. The Democratic Party, however, has been cautious, fearing the amendment debate could overshadow its push for sweeping reforms—including special investigations—amid ongoing partisan clashes.

Democratic Party lawmakers Lee Sung-yoon and Park Jie-won have both argued that constitutional reform is premature, insisting that accountability for alleged insurrectionary acts and completion of major reforms must come first. The People Power Party also warns that pushing amendment talks without broad social consensus could exacerbate political polarization, especially with judicial and election issues intertwined.

Experts largely agree on the need for constitutional reform but stress that restoring Parliament’s core functions is more urgent. As political tensions intensify, they argue, both amendment efforts and bread-and-butter legislation are unlikely to advance.

Political commentator Park Sang-byung cautioned that once constitutional talks begin, they could become a “black hole,” eclipsing all other policy agendas. “In a climate of extreme confrontation between majority and minority parties,” he said, “neither constitutional reform nor livelihood legislation can succeed. Structural cooperation is essential for progress on both fronts.”

#constitutional amendment #South Korean politics #bipartisan cooperation #National Assembly #presidential system

Copyright by Asiatoday

Most Read

-

1

-

2

-

3

-

4

-

5

-

6

-

7