|

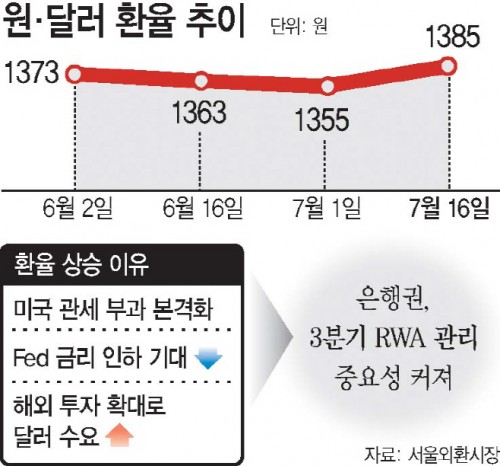

The won-dollar exchange rate, which had stabilized under South Korea’s new administration, is surging again in July, driven by external factors such as renewed U.S. tariff threats under President Donald Trump and delayed rate cuts by the U.S. Federal Reserve. A sharp rise in demand for dollars—due in part to increased overseas stock investment—has further fueled the uptrend.

As a result, domestic banks are facing increased pressure to manage their risk-weighted assets (RWA) in the third quarter. A sustained rise in the exchange rate could exert downward pressure on Common Equity Tier 1 (CET1) ratios. With tighter government restrictions on household loans pushing banks to expand riskier corporate lending for profitability, the burden of capital management is expected to intensify.

On July 16, the won-dollar rate closed the week at 1,385 won, up 5 won from the previous day’s close of 1,380 won. This marks the highest level since June 23, when the rate spiked amid Israel-Iran tensions.

Analysts attribute the latest jump to escalating tariff threats. On July 7, President Trump reaffirmed his plan to impose a 25% reciprocal tariff on Korean imports in a formal letter. This announcement has heightened market anxiety, driving demand for safe-haven assets like the dollar. Furthermore, the U.S. consumer price index for June came in at 2.7%, exceeding market expectations and diminishing hopes for a July Fed rate cut. As a result, the won is likely to remain weak in the short term.

Rising overseas investment by Korean investors has also increased dollar demand. According to the Korea Securities Depository, as of July 14, the total amount of overseas securities held by Korean investors stood at $188.6 billion (about 262 trillion won). That’s an increase of $7.1 billion in just two weeks—roughly 90% of June’s monthly increase of $7.6 billion.

The continued depreciation of the won is raising alarms in the banking sector. As foreign currency assets are converted at higher rates, banks’ RWA grow, making it more difficult to maintain CET1 ratios. Typically, every 10-won increase in the exchange rate lowers CET1 by about 0.01 to 0.03 percentage points.

With banks ramping up corporate lending amid the government’s household loan restrictions, their capital buffer management is likely to face further strain. Corporate loans carry significantly higher risk weights—averaging about 55%, compared to around 20% for household loans—making it harder to maintain capital adequacy ratios.

Most Read

-

1

-

2

-

3

-

4

-

5

-

6

-

7